Author: Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh

Published by: Penguin Random House India Private Limited 2019

ISBN 9353057108 978935305710 Pages 264

Price: INR 699.00

Reviewed by: Rupinder S Brar, MD FACC (Author of The Japji of Guru Nanak: A New Translation with Commentary. Published by Smithsonian Institution 2019).

I first met Nikky-Guninder Kaur, Crawford Professor and chair of Religious Studies at Colby College in 2017, during the golden jubilee celebration of the Sikh Foundation at San Francisco. Following her impressive lecture I voiced Wilfred Cantrell Smith’s contrarian view and asked her point blank if she thought Guru Nanak would think of himself as a founder of a new faith. I regretted it immediately, for too late I realized that mine was a contentious question for such a harmonious occasion. Even elsewhere, my question would have been unfair, one that many scholars would rather avoid. It is so because while the idea of Guru Nanak as a founder of the Sikhism is an article of faith for the community, scholars such a W.C Smith, Toynbee and Mcleod have questioned that fact. The topic is a potential minefield. Agree with these scholars, and one risked communal ire; disagree with them, and be open to charges of intellectual compromise and appeasement.

Fortunately for me, NGK was not offended by my question and instead gave a patient, reasoned reply. Now, three years later, she has done one better and calmly delivered a comprehensive and a thoroughly convincing rebuttal to any other doubters out there in her new book, The First Sikh: The Life and Legacy of Guru Nanak. The rebuttal begins with the title itself and she uses the Guru’s own authority (whom she refers to as ‘The First Sikh’ throughout) to make her point. Guru Nanak, she argues, was very clear that he stood at the beginning of something new, that is why he not only disclaimed any previous authority but started a brand new community at Kartarpur with new daily routines, new social conventions and new values. He bequeathed it to a new authority—a line of nine human successors.

‘What is so incredible about The First Sikh’ she writes, ‘is that he makes no exclusivist claims—the absolute One is the common ground—and yet splendidly triumphs in launching a distinct religious tradition remarkably vibrant centuries later.’ It is in such finely balanced language that she addresses all, the assenters and the dissenters, the scholars and the faithful. The First Sikh Guru she explains, indeed ushered a new faith but the novelty of his belief lay in rejection of all hierarchies of caste, class, region, religion or gender. To be Nanakian was not to only tolerate diversity but to actively cherish it. Nothing was strange and there could be no strangers.

I certainly found my personal question answered adequately in her first chapter itself but there is so much more. She seems to especially address two specific groups—the devoted scholars and the scholarly devout. For the community of the devoted, the book offers a new way to look at old dogmas, for the scholar a way to understand how the First Sikh was imagined and affected the evolution of that community. Time and again she sidesteps the mythical verses history argument and quotes extensively from the Guru’s own verses to focus instead on the real and the authentic, evocative and the personal, to highlight the remarkable legacy of her subject.

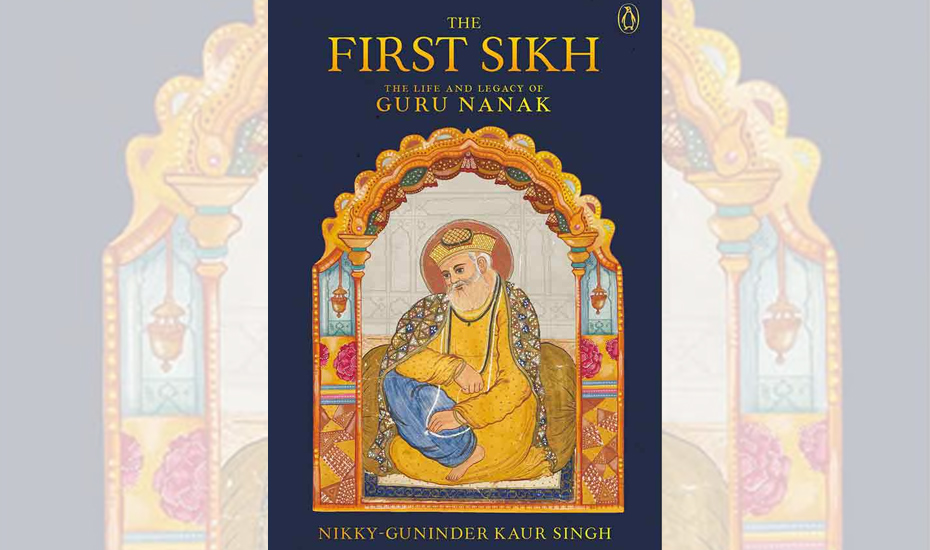

Her work is scholarly but her style is imaginative and narrative spellbinding. She is at her personal best while discussing the Janamsakhi literature and the Sikh devotional art over the preceding centuries. A lesser author could easily have ensnared herself and the reader into a hopeless maze of murals and miniatures, anecdotes and stories, some accepted as historical events others too fantastic to believe. Not so with NGK who charms her way through, sidestepping both the literal reading on one hand and the scholarly skepticism on the other to create a uniquely immersive experience by weaving the oral narratives with the sacred scripture, the painted pictures with the musical aural into a masterly narrative.

Somewhere along the line during her retelling the Professor disappears and an authoritative art critic emerges. Her attention to descriptive details brings to mind Sister Wendy Beckett whose hugely popular 1996 BBC series—Sister Wendy’s Story of Painting made her a household name as she brought the renaissance art to life for many who otherwise lacked the confidence to enter an art gallery. Similarly, NGK’s narrative on the Janamsakhi literature and art is not merely information and knowledge but an experience in itself—educative and uplifting, simply transcendent. The only complaint a reader should have is the absence of pictures in the chapter that discussed art so eloquently. Addition of only a few would have enhanced the narrative exponentially.

Fortunately, she makes up for this one shortcoming elsewhere for her detailed description of sacred Sikh art is matched by her capacity to faithfully translate Gurmukhi poetry, both sacred and secular into English in such a way as to not only retain the meaning but enhance the beauty of the verse itself. For example, she translates Shiv Batalvi’s poem on Guru Nanak in the following words:

Traveling far and wide he settled in Kartarpur….

An Ascetic’s outfit he wore no more,

He seated himself in this world,

He who could do miracles, worked with his hands…

The world lit up…

The four corners burst forth…

Uh Raab hai ikk oankar…

That Divine is the One Being!

Reading such lyrical passages one can easily forget that this book is first and foremost a work of high scholarship but that’s what it is. NKG has an enviable mastery of the Sikh scriptures that is matched by her impressive knowledge of western philosophy and literature. She effortlessly quotes Wittgenstein and Whiting, Salman Rushdie, El Saadawi and Valerie Kaur throughout the book to demonstrates why Guru Nanak remain relevant in the 21st century. By the time one is finished reading Guru Nanak not only becomes a familiar figure but also a contemporary one.

She skillfully unpacks the seemingly stark verses of the Japji to dig out previously overlooked concepts to construct a solid framework of the Nanakian philosophy. One can almost hear a goldsmith hard at work in his smithy as Guru Nanak’s 16th century metaphors come to life. Welding a hammer of knowledge against the anvil of wisdom the artisan imprints the sacred Naam on the the psychic self as he beats the ego out. One can further conjure up an image of a new loving and fearless, spite less, spotless self emerging in real time that not only tolerates but celebrates the diversity of creation—that is the Gold standard self, one that has now become the personification of the Divine One.

Many such metaphors abound, but what makes this book so unique is the author’s extraordinary capacity to draw attention to concepts that have been ignored by almost everyone else before. For example, NGK is perhaps the only writer to highlight the gender inclusive Divinity that lies at the core of Nanakian theology. Using parables and quotes from the Guru’s own writings, she

questions a patriarchal reading of the Guru’s words by Sikh scholars from GS Talib to Gopal Singh who she argues have been complicit in softening their feminine references and inadvertently perpetuating a masculine culture. She strongly argues for a complete ‘disclosure of feminist possibilities permeating the SGGS’ inviting future scholarship in this regard. The final chapter examines the Nanakian legacy through the works of fine artists—musicians and artists, singers and poets ranging from Aparna Caur to Allama Iqbal. The book ends on a celebratory note. The best is yet to come.

There is perhaps one other minor shortcoming in the current book and that is the frequent use of overly specialized terminology which makes the otherwise marvelous text difficult to follow at times by the lay reader. It is perhaps unavoidable to some extent given that the author is a tenured Professor whose first duty is towards her more erudite student scholars. Unfortunately, the very same vocabulary that makes Guru Nanak accessible to a trained scholar makes him remote to all others and one wonders if a middle ground may not be more desirable in the future. For example, many lay readers may not recognize the word ‘soteriology’ which can easily be substituted by a closely related but more easily understood one, ‘salvation’.

However, this is a minor quibble.

Professor Singh has written a highly readable yet authoritative book that should be of interest to all those engaged in examining the life, teachings and the legacy of Guru Nanak. There have been several other such works over the years, notably by historians H. McLeod and J. S. Grewal in the past and more recently by well known authors Roopinder Singh and Navtej Sarna. One may even include the laudable effort by the young Pakistani writer, Haroon Khaled in this category. Among the authors specializing in Nanakian studies however, Nikky Guninder Kaur Singh stands out as the most impressive—both cerebral yet poetic at the same time. Discussing another such author, she herself had written elsewhere that:

“There surely is a close bond between a reader and author, and reading, as we all know, is much more than just a cerebral process. But when the writer happens to be one’s own father, the text becomes a more powerful medium, and the author-reader relationship acquires a greater intimacy.”

The author under discussion was of course her father, the renowned Sikh scholar and historian, Late Sardar Harbans Singh. Sikh theologians are understandably guarded about the idea of reincarnation but believe instead that kindred spirits can pass on to worthy successors as in the case of the Sikh Gurus. Reading Nikky Guninder Kaur Singh’s latest book one is tempted to believe that the scholarly soul of her father seems to have passed intact into her for with it she has established herself as one of the foremost Nanakian scholars of our time.

Reviewed by: Rupinder S Brar, Punjabi American Heritage Society, Yuba City, California

(Author of The Japji of Guru Nanak: A New Translation with Commentary).

Available on Amazon.com