BY SARAB KAUR ZAVALETA

(website: seamlyfilms.com – for film in development)

I was a little girl in 1947 during the Partition, and although I remember a couple of isolated events, I did not understand what was going on. Why all the grownups seemed so agitated and careful about where they went and who they talked to. Normal talk within the house often turned to whispers. My father, Sardar Jagjit Singh, who was working for the British railways in India, was put in charge at the Lahore Station, and he used to invite us occasionally to come visit him at his office at the station, give us drinks and cakes and let us see all the goings on at the station.

These visits were happy ones full of excitement at the prospect of seeing one of the famous trains pulling in – the Frontier Mail, the Toofan, The Grand Trunk Express and so on. For us it was great entertainment to see the English ladies dressed in all their finery getting off their luxurious salon wagons, walking their dogs, with personal bearers running around bringing tea and attending to their needs. Our father stopped our visits. The only explanation we got was that it was no longer safe for us to go to his office.

Sometimes we would hear a lot of shouting from the streets and people shouting slogans. Even that got more frequent and we were frightened. One day my father came home and told my mother to get ready to leave for Simla to stay with our aunt and uncle, that it was no longer safe for us to stay in Lahore. Many non-Muslim families were getting killed and Sikh families were a special target. So in a few days we went to the station with our luggage. It was very crowded, with lots of police, and groups of people shouting “Pakistan Zindabad” (“Victory to Pakistan”) and waving swords. We felt very frightened. My father met us there and when a train pulled into the station, my father led us to the special salon wagon reserved for us to take us to Amritsar. He did not come with us, and we were sad and crying when the train pulled out of the station. There was my father standing at the station in his black uniform studded with many gold buttons, and a baton in one hand, with a turban and beard, looking very handsome, waving out to us with wet eyes. We did not know when we would see each other again. Later I learned that he was not sure we would get safely to Amritsar, as many trains were stopped along the way and people hacked to death. But we were the lucky ones to get to our destination safely. We got to Simla to my aunt’s home, who had no children of her own, and doted on us but disciplined us with an iron hand. She would make us sleep wearing three dresses, our hair tightly braided, and shoes near the bed, in case we had to run in the middle of the night.

It was my father who was caught in the middle of a very bloody ordeal. There were riots almost everyday at the station, with people killed here and there. It became an uncontrollable situation and trains were so crowded that they could barely move. The roofs of the trains were filled, and people hung on to anything they could grab on the train, door knobs, railings, window guards, with bundles of possessions on their arms, filling the sides of the trains, hanging on for dear life.

Sadly so many of them were butchered in the riots or on the way to the Indian border. My father saw the danger mounting and asked his British bosses to be transferred to Amritsar in India to receive the incoming refugees. In Amritsar when the trains came from the Pakistan Punjab side, there were very few people left alive. It was even difficult to open the doors and windows that were caked shut with blood. This was an unimaginable nightmare.

My father had to organize the transfer of dead bodies to a cremation ground. Those left barely alive were sent to refugee camps. My father saved many lives, and allowed some of the refugees to stay at our large Railway home and in its servants’ quarters, until they found their relatives and moved on to other places.

There were other families my father knew, who he never saw again. He received the news that a whole train had disappeared on its way from Rawalpindi to Lahore. The father-in-law and brother of a Parsi family, our family friends, were travelling in it. That train was never found. The same Parsi friends also lost a son and father, butchered on another train while they slept. Another friend’s sons, Harcharan and Gurdial escaped by cutting off their hair and beards in the Muslim fashion, walking for fifteen miles, then hiding in a military truck to get to the border. (Later Haracharan married my eldest sister). Entire families were killed, and many women and young girls were raped and then hacked to death. The best of friends, regardless of religion, became enemies overnight.

Did the British care? They sent a man, Radcliffe, to set the border lines between India and Pakistan. He had never set foot in India, and without much study of the region, the culture, a line was drawn arbitrarily to divide the two countries. There was no organization of a peaceful transfer. The British just walked away from it all, leaving the Indians to their fate. The result was butchery and bloodshed. A country was created for Muslims, and yet more Muslims opted to stay in India. Was this Partition necessary? The biggest migration in history took place, over 20 million displaced, and over two million dead. No one could prevent this horror.

My mother’s cousin and her husband and baby had to escape by foot in the heat of August. They had little to eat. Her husband was killed before they could even cross the border. She and her son had to starve for days. They never fully recovered their health, and she had to depend on help from relatives to live. Similarly my mother’s brother (our Mama) and his family had to walk across for miles and miles in horrible conditions, they witnessed skirmishes on the way, much killings, but were lucky to have survived. They saw the discomfort of old people walking and dropping dead, babies being born and mothers dying as no food was available for them and no milk.

For our parents and their generation it was such a horrendous trauma, that they could not talk about it for years.

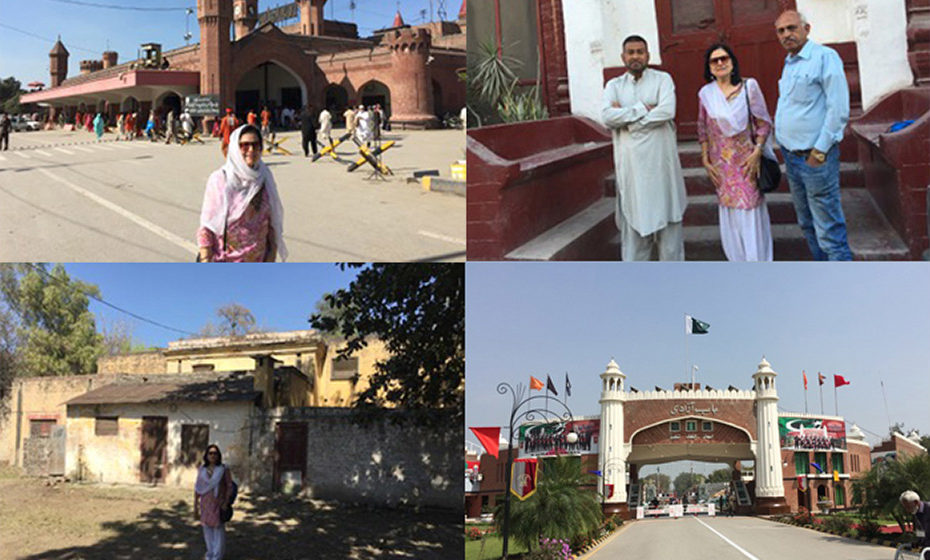

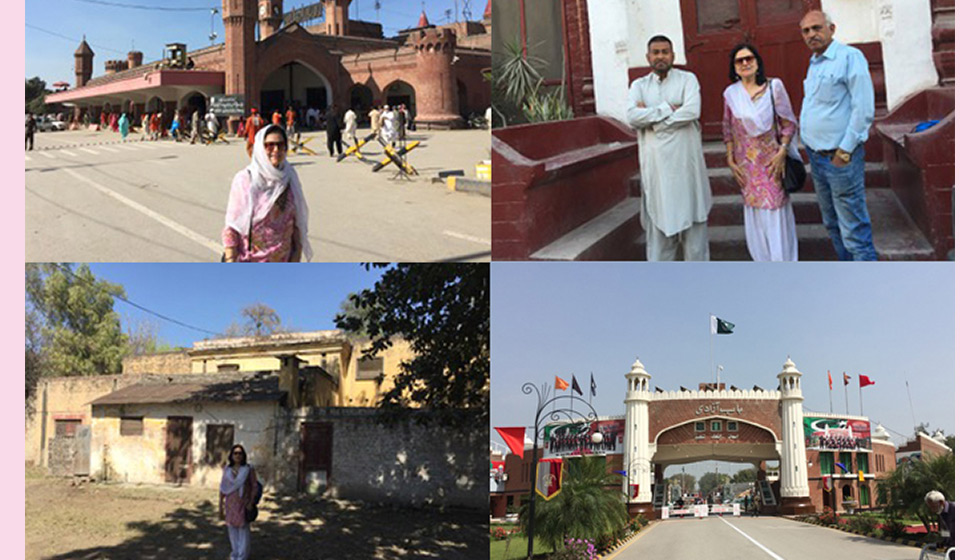

I made two journeys to Pakistan to do my research and learn something about my roots. I found the properties of my father’s family in the old walled city of Lahore. They owned many homes, some have been converted to more modern structures. One house is still there, beautifully preserved with its original architecture and stained glass windows by the present owner, a young lawyer who told me that one of my grandfathers sold it to his family in the early 20th century, and he gave up his law practice to live there and keep it in its original design.

Then I met some older men sitting around a small dhaba (tea shop), who were surprised when I approached them. They asked me to return in the evening when they would have a couple of elderly people who could tell me stories of my family. I returned later with a professor from Lums University in Lahore and a Sikh historian who was a Muslim. The elders told me that my great great grandfather’s legend still lives on in the old town. Jawahar Mal was one of the favorite ministers of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, an elephant used to come every morning from the Court of the Maharaja to pick him up, and then he would return on the elephant in the evening. It was a spectacle for the people in the city at that time. I got such a chill hearing this and learning more about my family. The Sikh historian confirmed the story, and was then able to link my family history to other grandfathers who were engineers and soldiers and fought several wars in Persia (Iran) and Mesopotamia (Iraq/Syria).

Another time I walked through the dusty Anarkali Bazaar, which did not seem to have changed much, where I got lost at the age of 2, until finally my parents found me!

Then I also visited the Station Master’s home near the railway station, and again it was so surprising to see that the large home built in the British Colonial style was still there, unchanged, but somewhat old and dilapidated. The banyan tree that an older sister had told me about, was still there in the backyard. As I walked through the empty house, I imagined the voices, footprints and fingerprints of my parents echoing through my body. I could picture my mother in the front garden, giving instructions to the gardeners what flowers, vegetables and fruit trees they were to plant. The smell of jasmine flowers made her presence so strong in my mind. It was so emotional that I shed some tears, thinking of what my parents must have suffered through the Partition, having to leave everything behind and starting a completely new life with none of their possessions.

I also visited Kotli Laharan, near Sialkot, where my mother’s family had large havelis, with private water wells in the inner courtyards. They had big farmlands nearby that grew mangoes, wheat and mustard. A 90-year old man, who I met there, showed me around and told me that the mangoes from my grandfather’s farm were the best and most famous in all of Punjab. He was about 18 years old at the time of Partition, and had worked for my family. Seeing me brought tears to his eyes and memories of his “happy” youth with the protection of my family members. He took me to the school which my mother had attended until the fifth grade – when education ended for women. How emotional that was for me, to imagine my mother and her two older sisters there as young girls. He also showed me the school for boys, just on the edge of the big village. When I left, many people had gathered to say goodbye, and yes I shed tears with them, hoping that I would return one day and find them all there.