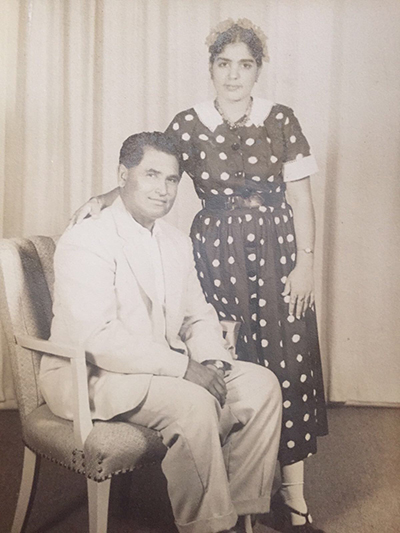

Wedding Photo, Punjab, India, 1979. Courtesy of Pushpinder Kaur

By Vidya Pradhan

When 24-year-old Harbhajan Kaur Purewal’s marriage was arranged, she expected to make the once-in-a-lifetime migration most Indian women are familiar with – leaving the safe, warm, known home of her parents to the unknown world of her in-laws. Perhaps the folk song Jutti Kasoori would be sung at her wedding, conveying the plaint of the new bride –

Jutti kasoori, paeri na poori,

Haaye rabba ve saahnu turna peya

Jina rahaan di main, saar na jaana,

Ohni raaheen ve saahnu murna peya

These shoes from Kasoor, they don’t fit well on my feet

But I have to walk in them

These roads are unknown to me

But I have to follow them.

(Kasoor is a district in Punjab known for its footwear)

But Harbhajan’s journey to her new home in 1954 would take her over 7,000 miles away to Lodi, California, where her husband Bakhtawar Purewal farmed 43 acres of land with his brother in the rich Sacramento Valley. Hailing from a conservative Punjabi family, Harbhajan had never set foot outside her house without the escort of her brothers or her father, and now she made the long journey to America all by herself, to an unfamiliar home, culture, and country.

Scores of women like Harbhajan made the trek from Punjab to the United States in several waves, beginning in 1910. When U.S. immigration laws were tightened, wives were separated from their husbands for years, often bringing up children in Punjab by themselves. After 1965, when immigration laws were eased, a new wave of family migration brought the wives to join their spouses. These women, like the ones before, faced the daunting task of adjusting to a country where their clothes, their cuisine, and their language immediately set them apart from their neighbors.

Despite the odds, these women bonded and formed a strong and supportive community, helpmeets to their spouses on the farm, and sisters to their fellow countrywomen at the gurdwaras. Says Sharon Singh, Harbhajan’s daughter, “My mother was told to assimilate, blend in, fit in.” Harbhajan received this sage advice from Nand Kaur, one of the earliest migrants from Punjab, having come to the United States in 1910. For Harbhajan, like many of the other wives, fitting in meant exchanging her traditional salwar suit for western clothing, and here she received support from her spouse, who understood the need to not make any waves in their rural community.

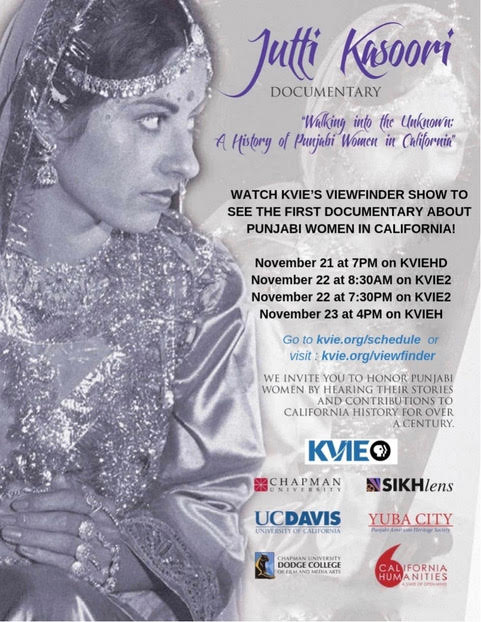

Harbhajan’s story, as well as those of several of those pioneer Punjabi women, has been told in Jutti Kasoori, the new documentary by Professor Nicole Ranganath and her team at UC Davis. The 30-minute documentary, subtitled “Walking into the Unknown – A History of Punjabi Women in California” is the first of its kind to focus on the unsung heroes of the community. It is the result of 24 in-depth interviews with women ranging from the older generation that lived through the partition of India to their daughters and granddaughters who were the first generation born in America.

“When Indian women arrived in America, they had already migrated once before as young brides when they left their parents’ homes to go live with their husbands and their families,” says Ranganath, who co-produced and directed Jutti Kasoori. “From birth their mothers had prepared them for this journey after marriage. But the journey that these women made to the States was unexpected and they showed incredible resilience, forbearance, and courage towards the challenges that they faced.”

Each woman who arrived and adjusted became a lifeline to the ones that came after. Some women learned to drive, and helped the newer arrivals with grocery shopping and translations. All of them worked alongside their husbands in the fields while taking on the full responsibility of home and hearth. In what was a typical life for these strong women, another Harbhajan, Harbhajan Kaur Takher, irrigated her family’s land, hauled peaches, and drove the younger women to the hospital for their deliveries.

Archival work on the Sikh community has been about the male Punjabi farmers and entrepreneurs till now but “nobody talks about the women,” says Ranganath. “Not only did they help their families in the fields doing hard labor, but they were the pillars of their community. More recently, Punjabi American women have made huge contributions in the fields of medicine, politics, and education.”

The documentary also pays attention to the issues that the younger generation of Punjabis, brought up in close ethnic communities, grapple with as they adjust to the American society where they belong by way of citizenship.

“I want this documentary to be a part of the California school system,” adds Ranganath. The half-hour duration of the film is deliberately structured to fit into a class session. “It is important that this vital part of California’s history be preserved and remembered.”

Her project was aided by the invaluable contributions of three women whose mothers and their friends were featured in the movie – Davinder Deol, Raji Tumber, and Sharon Singh. These women persuaded the reluctant older generation to open up and share their experiences, a daunting task because many of the women did not think their lives were special or that anything they had to say would be important or interesting.

Thanks to the efforts of Professor Ranganath and her team, these histories have been preserved in the documentary, and not a moment too soon. Half of the women in the above picture, whose stories have been documented in Jutti Kasoori, have already passed away. Among those that left us include Harbhajan Purewal, pictured here in a black shawl.

Jutti Kasoori was possible due to a grant from the California Humanities and the deep collaboration between UC Davis, Sikhlens, the Punjabi American Heritage Society and the broader Punjabi American community.

Jutti Kasoori has aired on the local PBS affiliate, KVIE. To watch online, go to kvie.org/viewfinder. The documentary will be available for classroom viewing in the coming months.

Coming soon: To learn about the women featured in this film and others